Arc of a Song: On Broadway

- John Corcelli

- Jun 5, 2016

- 5 min read

In the history of Popular Music, or music written since 1900, we currently enjoy an evolution of over 100 years worth of the art of the song. I’d like to take a look at one song “On Broadway” and four contrasting versions that reflect the times in which they were recorded.

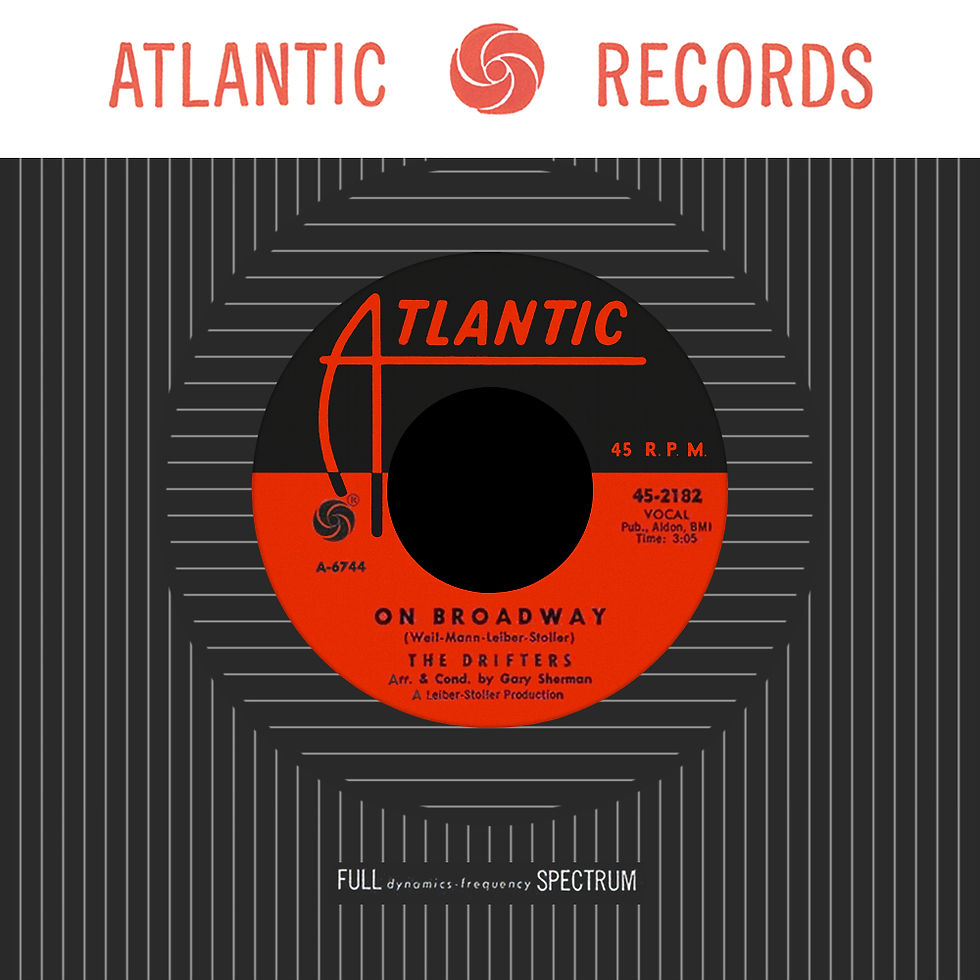

Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann wrote “On Broadway”, two of the most successful songwriters to come out of the famous Brill Building, the songwriter’s haven of New York City. It was first recorded in 1962 by a girl-group known as The Cookies, whose version was more of a light novelty pop song. Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, who shared an office with Weil and Mann in the Brill Building, took the song to a different, now familiar, version setting the tune to an R&B rhythm and changing the phrasing to reflect an more nuanced and personal story about a young person looking for hope “on Broadway”. The result of Weil/Mann/Leiber/Stoller collaboration was the remarkable 1963 recording by The Drifters.

When The Drifters released their version of “On Broadway”, they were an established R&B group who already had a string of hits. The single peaked the Billboard Top 100 at No. 9 but its sound, feel and vocal honesty, particularly during 1963, is a poignant version, one that I never tire of hearing. It’s also notable for the guitar solo by a young musician named Phil Spector.

The Drifters recording was released during a time when Black American youth was searching for identity and artistic equality in White America. John F. Kennedy was President and Broadway was the geographic location of that success, best summed up in the words, "I won't quit til I'm a star, on Broadway". It’s a version that offers young, Black Americans hope in the sea of racial inequality. In this beautifully balanced recording, the sound of hopefulness is musically reflected in two key changes: once after the first verse and again after the second. It then settles into a nice groove with angelic “on broadway” responses from the rest of the group. To me, The Drifters sing about tenacious ambition.

More recordings were made after 1963 by MOR singers such as Bobby Darin, Freda Payne, Blossom Dearie and the Dave Clark Five. But they didn’t come close to the rapture of The Drifters recording. (Some songs are better left alone)

Then, in 1978, jazz guitarist and singer, George Benson released Weekend in L.A. (Warner Bros) that included “On Broadway”. Benson’s interpretation is as far from New York as possible on this very successful live album. He released it as a single that went to No. 7 on the Billboard Hot 100 in an edited form. The 10-minute version, from the LP, features a keyboard solo after the guitar solo, with an excellent groove laid down by Harvey Mason, drums and Ralph McDonald, percussion.

Reviewed in Rolling Stone, issue #261, critic Bob Bluementhal raises an interesting point about Benson’s career in 1978: “on the surface, George Benson’s career has followed a pattern established by Nat King Cole and Ray Charles: many dues-paying years as an instrumentalist, then the big payoff with the emphasis on vocals…on this live album, Benson sounds like an unknown soldier in that non-descript legion of black crooners who once or twice came up with a hit…and were then forgotten. But “On Broadway” works better with its meaner groove, guitar/scat vocal and a model percussion duet.”

For me, Benson’s version takes the song to the next level. While The Drifters sing about getting to the top, this version is sung from the top because Benson, after years of hard work as a sideman, has made it and wants to share the love. Faithful to the original, with more subtle key changes, Benson’s version became even more popular to mainstream audiences after its use in the film about Bob Fosse called, All That Jazz. For some people it has become synonymous with Benson, who still includes the song in his set list.

Ten years after Benson established his “On Broadway” groove for the ages, Neil Young & Crazy Horse recorded their more hostile version on Freedom, (Warner, 1989) a decidedly contemporary take, garage-band style. There isn’t much hope in this version, because Young is more interested in singing about the dirty side of New York than any fulfillment of the American Dream, especially after Ronald Reagan. (Hopelessness is just one of the themes running through Freedom.) But taken another way, he’s co-opted the song making it a rock version of an R&B hit, laid to waste by the heavier sounds of the White establishment, not necessarily Young himself. This hijacking of Black music by White artists was especially prominent in the 1950s. One glance at the work of Pat Boone stealing the sexual heat and financial rewards of Little Richard serves as a sad reminder of those dreadful times.

Perhaps Neil Young knows this. His head-bobber version has a punk sensibility but I'm not entirely convinced of Young's "fuck you" attitude on this version with Crazy Horse. Young's vocals are way back in the mix with a ton of reverb that reflects the Drifters recording, but there's not a speck of a nod to Benson anywhere to be heard. Nevertheless the song diverges into a distorted hell that certainly smashes all the ideals laid out by The Drifters some 25 years earlier.

This is a song without any glitter to be found, with the grime so deep you can trace your finger through it and it will come out black. As critic David Fricke comments in Rolling Stone #564, [this version] “is delightfully perverse, Young strangling his guitar with dramatic conviction…captures the competing strains of agony and ecstasy running all through Freedom…so much for fairy tale endings.” Perverse? Yes. Delightful? No.

In 2011, quite possibly rebounding from the events of 9/11 in New York, Jazz vocalist Tierney Sutton released a decidedly positive album called American Road (BFM). The record features songs from the American songbook either folk tunes (Way Faring Stranger, Shenandoah, Amazing Grace) or Broadway (Summertime, It Ain’t Necessarily So, Something’s Comin). Everything on here has been reinvented to suit Sutton’s voice and open up the music to new interpretations. It also features On Broadway in a cautiously buoyant and inspired version that breaks free of the past and, unlike Neil Young, looks forward.

The song is shaped by the minimalist piano introduction by Christian Jacob using some slightly dissonant chords with a syncopated rhythm that’s very close to the George Benson version. To my ear it sounds like the pulse of New York City traffic. It’s contrasted by a dreamy vocal as Sutton raises the tension by ending the first and second verse as a musical question. The “one thin dime” on verse one and “can play this here guitar” on verse two linger for a couple bars like they’re floating above Broadway only to be brought crashing down to earth by the funky beat of drummer, Ray Brinker. In a clever move, she also changes the gender to reflect her perspective as a woman, looking to “make some time” with the men, who, according to the song, give her “the blues.”

This version is probably influenced by Sutton’s Ba’hai faith: a doctrine that preaches about the unifying forces of God, religion and humankind. For Tierney Sutton then, On Broadway represents a unifying spirit that can literally carry you from place to place beyond the geographic confines of Manhattan. Religious or not, it’s an excellent version full of adventure.

“On Broadway” is an enduring song because it’s been recorded over a period of 50 years and remained relevant. The four recordings discussed here, are as different from one another as you can get. Taken as a whole they have, what the late Art critic Robert Hughes calls “fluctuations of intensity” resulting in an emotive sensibility of time and place mirroring American history and our connection to it, for better and worse. [This essay first appeared on critics@large in 2013.

Comments